Hey, y’all!

In today’s letter we are covering, First who then what and Confront the brutal facts. In the audiobook each one of these chapters take a full hour. I have tried to trim it as much as I could but broke the 5 minute rule.

This one clocks in at an estimated read time of 7 minutes.

Packards law

There's this thing called "Packard's Law," named after David Packard, the co-founder of Hewlett-Packard. It's basically the idea that a company can't grow its revenue faster than its ability to get the right people to make that growth happen. If you try to grow too fast without having the right team, you just can't build a great company. The main factor that affects a company's growth isn't the market, technology, competition, or products - it's having enough of the right people on board.

First who then what

The top leaders in great companies start by getting the right peeps on board, then figure out where to take the business. It's all about the "who" before the "what." Some companies have a genius leader with lots of helpers, but when the genius leaves, things go downhill.

Great leaders are super careful with their choices, but they're not cutthroat. They don't rely on firing and restructuring to make things better. There are three simple rules they follow:

If you're not sure, don't hire – keep searching.

If you need to make a change, do it. Just be sure you're not putting someone in the wrong spot.

Put your best people on your biggest chances, not just fixing problems.

Great teams have debates to find the best answers and then stick together once they decide. And guess what? We found that big paychecks don't always make a company great. It's about having the right people, not just any people. The right people have the right character and skills, not just a fancy background.

For a company to go from good to great, they gotta face the hard truths about their situation. Being honest makes the right decisions super clear. You need a culture where everyone can speak up and the truth comes out. There are four ways to do this:

Ask questions, don't just give answers.

Have conversations and debates, not forcing ideas on others.

Look into what went wrong without blaming anyone.

Set up systems that make sure important info gets noticed.

Great companies handle tough times better than others. They face reality and come out even stronger. One important mindset is the Stockdale Paradox: Believe you'll make it, but face the tough stuff head-on.

Surprisingly, being super charismatic can be bad, because people might be scared to tell you the truth. Leadership isn't just about having a vision – it's about making people face the truth and act on it. Trying to "motivate" people is pointless. If you've got the right people, they'll be self-motivated. Just don't de-motivate them by ignoring the harsh reality!

Getting the right people on the bus

So, Jim Collins found something pretty interesting when researching companies that went from good to great. Instead of setting a new vision or strategy and getting people on board, these successful execs actually focused on getting the right people on their team first. They figured if they had the right people, they'd be able to take the company somewhere great, even if they didn't know exactly where yet.

Take Wells Fargo, for example. Their CEO, Dick Cooley, started building an amazing management team way back in the 1970s. He didn't know what changes were coming in the banking industry, but he knew that having top talent would help them face whatever challenges came their way. And when those challenges did arrive, Wells Fargo handled them better than any other bank.

Bank of America, on the other hand, chose a different approach. They used a "weak generals, strong lieutenants" model, which led to a less effective management climate. It wasn't until they started recruiting strong leaders from Wells Fargo that they began to improve. But by then, Wells Fargo was already way ahead of the game.

Nucor hires badass farmers

Jim Collins found a great example in Nucor, a company that believed you could teach farmers how to make steel, but you can't teach work ethic to those who don't already have it. So, Nucor built its mills in places like Crawfordsville, Indiana, and Norfolk, Nebraska, where hardworking farmers lived. Nucor made sure only people with a strong work ethic stuck around by having high turnover at first, but then a steady group of dedicated workers remained.

Nucor paid its workers more than other steel companies, but it tied their pay to team productivity. This approach meant hardworking employees thrived, while lazy ones were pushed out. In one case, workers chased a lazy teammate out of the plant! Nucor didn't believe people were the most important asset; they believed the right people were.

Jim Collins noted that good-to-great companies like Nucor focused more on character attributes than specific skills or knowledge. They saw traits like work ethic, intelligence, and values as more important and harder to change than teachable skills.

One good-to-great executive even said that his best hiring decisions often came from people with no industry experience. In one case, he hired a former POW who had escaped twice during World War II. He figured if someone could do that, they could handle business challenges.

Rigorous not ruthless

Jim Collins found that good-to-great companies can seem like tough places to work, but they aren't ruthless; they're rigorous. Ruthless means cutting people without thought, while rigorous means applying strict standards consistently, especially for upper management. This way, the best people can focus on their work without worrying about job security.

Being rigorous in people decisions means focusing on top management first. Jim Collins worries that people might use "first who rigor" as an excuse to blindly cut people, which would be a mistake. Good-to-great companies rarely used layoffs as a tactic and never as a primary strategy. In fact, layoffs were used five times more frequently in the comparison companies.

So, the key takeaway is that the path to greatness isn't about mindlessly cutting people; it's about being rigorous and focusing on having the right people in the right positions.

Confront the brutal facts

Back in the 1950s, there was this huge company called A&P, which was like the biggest retail organization in the world. It was even one of the largest corporations in the US, second only to General Motors in sales. Kroger, on the other hand, was just an average grocery chain, less than half A&P's size and not really outperforming the market.

Then the 1960s came along, and A&P started to struggle while Kroger began transforming into a great company. By the next couple of decades, Kroger generated returns that were way better than A&P's. So, what happened? How did Kroger pull this off, and how did A&P go from being awesome to awful?

Well, A&P had a business model that worked really well in the first half of the 20th century when people just wanted cheap groceries in simple stores. But as times changed, people wanted more than just basic grocery stores. They wanted huge superstores with all kinds of products, services, and conveniences.

Now, you might think, "Alright, so A&P just couldn't keep up with the times and got left behind." But here's the thing: both Kroger and A&P were old companies, and they both had pretty similar starting points in the 1970s. The difference was how they responded to the changing world.

A&P was kind of stuck in the past, trying to hold onto their old ways. When they did try something new, like opening an experimental store called The Golden Key, they ended up shutting it down because they didn't like the answers it provided. A&P kept looking for quick fixes and jumping from one strategy to another, but never addressed the core issue that customers wanted different stores.

Meanwhile, Kroger took a different approach. They experimented with the superstore concept in the 1960s and realized that their old-style grocery stores would eventually go extinct. Unlike A&P, Kroger faced this reality head-on and took action.

When Jim Collins, the author, asked Kroger's CEO Lyle Everingham about the factors behind their success, he found it pretty obvious. They did extensive research, saw that superstores were the future, and made the necessary changes. Kroger overhauled its entire system, transforming every store and leaving regions that didn't fit the new vision.

By the 1990s, Kroger had become the number one grocery chain in America, while A&P still had tons of outdated stores and had become just a shadow of its former greatness.

Climate of truth

Hey there! Wanna know how to create an environment where truth is heard? Here's a casual rundown with some bullet points:

Lead with questions, not answers:

Take a look at Alan Wurtzel, who transformed his company by asking questions instead of providing all the answers

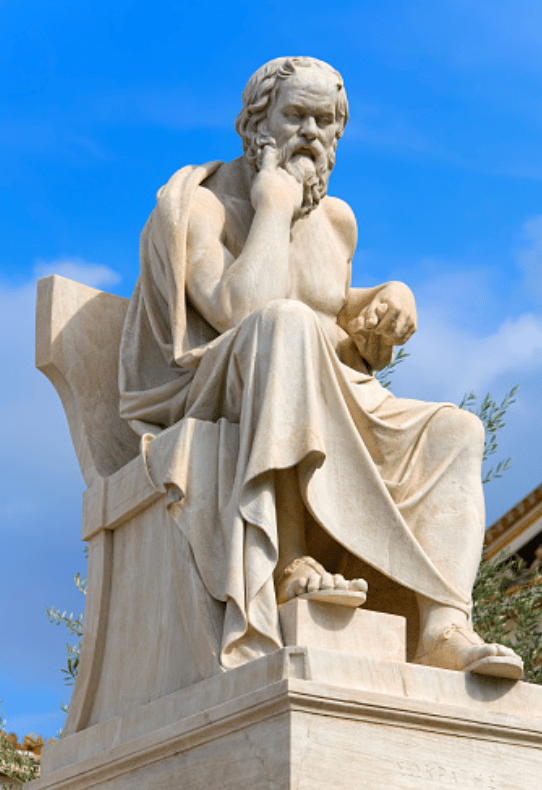

Good-to-great leaders use a Socratic style, using questions to gain understanding and foster open discussions

Engage in dialogue and debate, not coercion:

Nucor, a successful steel company, was built on heated debates and discussions, led by their CEO Ken Iverson

Good-to-great companies thrive on intense dialogue and healthy conflict, as they search for the best answers together

Conduct autopsies, without blame: At Philip Morris, after a bad acquisition, they examined their mistake without pointing fingers, focusing on learning from the experience

If you have the right people on your team, you'll rarely need to assign blame; just focus on understanding and learning

Build "red flag" mechanisms: Companies often stumble not because of lack of information, but because they fail to confront the truth

The key is turning information into something that cannot be ignored, so that leaders are forced to face and address challenges head-on

Remember, it's not about having all the answers or knowing everything. It's about being humble, asking the right questions, and fostering a healthy environment for open discussions and learning from mistakes. Happy leading!

Stockdale paradox

The Stockdale Paradox comes from Admiral Jim Stockdale's experience as a prisoner of war for eight years during the Vietnam War. He observed that the POWs who survived and stayed mentally strong were the ones who managed to balance these two mindsets:

Unwavering faith: They never lost hope that they would eventually be free and return home. This faith gave them the strength and determination to keep going, even in the face of immense suffering and hardship.

Brutal honesty: At the same time, they acknowledged the harsh reality of their situation. They didn't delude themselves into thinking that rescue or release would come quickly or easily. By facing the facts, they were able to adapt and make rational decisions to survive the day-to-day challenges.

In "Good to Great," the Stockdale Paradox is applied to business leadership. Great leaders and companies are able to hold onto their long-term vision and confidence in their success, while still being brutally honest about the obstacles and challenges they face. This approach helps them tackle problems head-on, make tough decisions, and ultimately emerge stronger from adversity.

So, in a nutshell, the Stockdale Paradox is about striking a balance between unwavering optimism and tough realism. It's a mindset that can help businesses thrive, and it's also a powerful tool for overcoming personal challenges. By staying hopeful yet grounded, you can navigate through difficult situations and come out stronger on the other side.